This is the last of a three part series on different theories related to Third Culture Kids (TCKs) and repatriation. Note that these are theories, not facts. As we will see, the theories all have their own merits, but they don’t always agree.

Click here for Part I

Click here for Part II

Part III

Last week we discussed Paul Pederson model, which describes five stages of culture shock. In review, Pederson suggests culture shock begins in the honeymoon phase, when a person has yet to experience culture shock, then a “cultural incident” causes disintegration or disorientation and confusion. During the reintegration stage, the individual begins to resolve the cultural dissonance. In the autonomy stage the person develops a greater awareness of herself and others, and finally reaches the interdependent stage, which consists of a new multicultural identity.

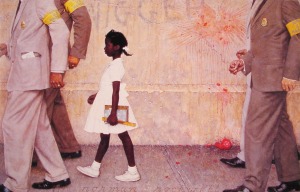

Though based on different populations, Pederson’s theory of culture shock is reminiscent of W. E. Cross’s* theory of Black identity development, called Nigrescence. The developmental theory consists of five stages:

- Pre-encounter

- Encounter

- Immersion

- Emersion

- Internalization

Let’s take a look at the similarities and differences between the two theories.

Pederson’s honeymoon phase, when a person has yet to experience culture shock, correlates with the Cross’s pre-encounter stage, when an individual has yet to develop an afro-centric identity. The Pederson’s disintegration and Cross’s encounter stage both involve a sense of shock and displacement, except in Cross’s model, this encounter has a racial basis. Unlike Pederson’s model, Cross includes an immersion stage, where a person immerses herself in African American culture, attempting to “embrace” the new Black identity and destroy the older, ignorant identity. We will discuss the significance of this stage to TCKs in the next paragraph. During the emersion and internalization phase (the 4th and 5th stages), an individual learns new behaviors and adopts values characteristic with being a member of Black society but develops a sense of comfort with people from all different racial backgrounds. The emersion and internalization stages align well with Pederson’s reintegration, autonomy, and interdependent stages.

There are obvious similarities between these phases, and indeed the experiences of African American and TCK young adults, except for one key phase—the immersion stage. The omission of the immersion stage may be credited to the difficulty TCKs face in achieving immersion, since strong post-repatriation communities have not existed in the United States. (Note however, that these kinds of communities are emerging, such as Mu Kappa for Missionary Kids, Global Nomads in the Washington Area, websites such as TCKid.com and certain groups on Facebook). One could ask whether successful autonomy and interdependence (Pederson’s terms) or emersion and internalization (Cross’s terms) rely on an immersion of some sort? Does the lack of immersion opportunities make finding a balanced identity difficult for TCKs? Some in the TCK community have written about an immersion experience in an affinity group or community, for instance, joining the Asian students’ association at university.

Let’s see how these stages might apply to Lisa’s (fictional) experience. This is the same story, with a few additions to fit the model.

Lisa, an American, Third Culture Kid, grows up in Egypt, Morocco and France. Her mother works for the American State Department. Like her mother, Lisa feels she represents the United States, and her mother often says, “You’re an ambassador as well!”

Lisa brings peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to school and wears Old Navy jeans on the weekends; she plays softball on the school team and friends joke about her American accent. Lisa represents the United States of America abroad.

The pre-encounter stage, when an individual has yet to develop an afro-centric identity.

Lisa can’t wait to return to the United States. Finally she won’t be the foreigner anymore! Her love of peanut butter, Old Navy and softball will be the norm, rather than the exception. No one will even notice her accent. Finally, Lisa will feel like she belongs—just as everyone fits in at home.

The encounter stage involves a sense of shock and displacement.

On the first day of school, Lisa meets her classmates. One girl says, “oh, you have such a cute accent!” Lisa lets it slide. Lisa has to fill out health forms, so she tells the nurse she is 170 centimeters tall and the nurse gives her a look. Lisa turns red, but lets it slide. After a short conversation, a boy says, “you’re kind of like a foreigner!” Lisa fights back tears and wants to go back to France.

Cross includes an immersion stage, where a person immerses herself in African American culture, attempting to “embrace” the new Black identity and destroy the older, ignorant identity.

Lisa joins the French club and becomes close to international and exchange students. She spends a lot of time online, learning about what it means to be a TCK and a global nomad. She also develops especially critical views of America and Americans; whenever an opportunity presents itself, Lisa separates herself from America.

During the emersion and internalization phase, an individual learns new behaviors and adopts values characteristic with being a member of Black society but develops a sense of comfort with people from all different racial backgrounds.

Lisa often tells people she’s a Third Culture Kid, but she begins to understand that her international background does not make her any less American, but does make her different from some of her peers. Lisa realizes she has many friends from many different cliques, and begins to explore how she is similar and different to her peers. This process can be draining, but is important to Lisa.

As Lisa learns what to expect from her friends and teachers, she begins to feel connected to her school community. She understands, respects and even cherishes both her American heritage and international experiences and actively keeps connections to both worlds.

* Cross, W. E., Jr. (1991). Shades of black: Diversity in African-American identity. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Posted by findingschools

Posted by findingschools